Strategy #4: You Can Strengthen Life-Span Relationships

Part 1 - The Need to Belong

Seven Strategies for Positive Aging by: Robert D. Hill, Ph.D.

Summarized by: Justin Hill, M.Ed.

You belong. Although there are times when you might feel that you don’t, if you think about your situation you will discover others who are interested in you and your well-being.

The need to belong is an emotion or a desire to be part of someone’s life; to be connected to others in some way.

Researchers suggest the need to belong is not only influenced by how many people you know, but is a subjective state that is affected by your:

People who suffer from a depressed mood may feel like they don’t believe, even if they are surrounded by supportive family or loved ones.

According to researchers (Baumeister & Twenge, 2003), the need to belong persists across the life span and is not the same for all people.

In fact, the need to belong can be so high for some people that they feel lonely even when surrounded by others.

On the other hand, people who possess less of a need to belong can be content with less personal connections (Stevens, Martina, & Westerhof, 2006).

The need to belong is a life-span construct that involves the following behaviors.

Interaction is a label for social exchange. Concern involves interaction that includes expression of awareness about your needs. Caring is showing not only a deeper understanding of another person’s situation, but also expressing a willingness to help as needed.

The need to belong is reciprocal in nature – it’s a give-and-take relationship that gains meaning from reciprocation.

Think about the people you know or have some connection with. The most important of those relationships involve the three belonging behaviors – interaction, concern, and caring.

The following exercise will help you understand how these three pieces work in your own life.

Summarized by: Justin Hill, M.Ed.

You belong. Although there are times when you might feel that you don’t, if you think about your situation you will discover others who are interested in you and your well-being.

The need to belong is an emotion or a desire to be part of someone’s life; to be connected to others in some way.

Researchers suggest the need to belong is not only influenced by how many people you know, but is a subjective state that is affected by your:

- Mood

- Health

- Self-perceptions

People who suffer from a depressed mood may feel like they don’t believe, even if they are surrounded by supportive family or loved ones.

According to researchers (Baumeister & Twenge, 2003), the need to belong persists across the life span and is not the same for all people.

In fact, the need to belong can be so high for some people that they feel lonely even when surrounded by others.

On the other hand, people who possess less of a need to belong can be content with less personal connections (Stevens, Martina, & Westerhof, 2006).

The need to belong is a life-span construct that involves the following behaviors.

- Interaction

- Concern

- Caring

Interaction is a label for social exchange. Concern involves interaction that includes expression of awareness about your needs. Caring is showing not only a deeper understanding of another person’s situation, but also expressing a willingness to help as needed.

The need to belong is reciprocal in nature – it’s a give-and-take relationship that gains meaning from reciprocation.

Think about the people you know or have some connection with. The most important of those relationships involve the three belonging behaviors – interaction, concern, and caring.

The following exercise will help you understand how these three pieces work in your own life.

Belonging Exercise

- Think of an important person in your life -

- Does this person show all three belonging behaviors?

- How do you show interaction, concern, and caring in this relationship?

- Think of someone you know, but don’t feel particularly attached to -

- How do belonging behaviors manifest themselves (or fail to show themselves) in this relationship?

- Identify an existing relationship that you want to enhance -

- How might you enhance your interactions with this person?

- How might you show concern?

- How might you show caring?

- Try to act on one of these belonging behaviors and observe how this relationship changes in response to your actions.

You don’t have to be physically present in order to belong, either. Think about how letters, talking on the phone, sending and receiving e-mails, and chatting on the Internet are ways to belong.

Research indicates that while a person’s need to belong is a stable trait, changes in one’s social circles will inevitably occur over time.

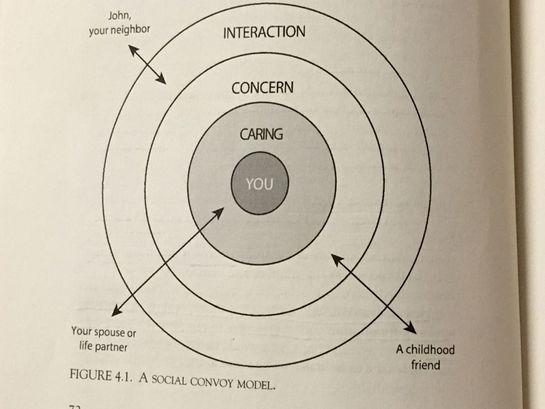

Antonucci, a gerontologist who studied social support in old age, coined the term social convoy to characterize the various relationships in one’s life (Antonucci & Akiyama, 1987).

The picture below is an example of a social convoy.

The center or the bull’s-eye in this diagram is “you.”

The interaction ring involves people who meet only the most superficial level of belonging. This area involves the interactions you have on a limited basis, like the neighbor you wave to, the coworkers you talk with at work, or people you encounter in your day-to-day travels like a bank teller or pharmacist.

The concern circle involves people who have not only interacted with you, but who have expressed concern about your welfare and in whom you are interested. This area may involve a childhood friend with whom you have regularly exchanged holiday cards, or a member of a senior center which you have attended regularly.

The caring and you areas of the circle involve people who not only interact and are concerned about you, but who care about you as well. These include family members, close relatives, your life partner, or your best friend. These are the highly meaningful people who have directly met your need to belong in the past and who are sources of support for you in the present and future. They are there when you need them, and they have been there through all three of the belonging behaviors: interaction, caring, and concern.

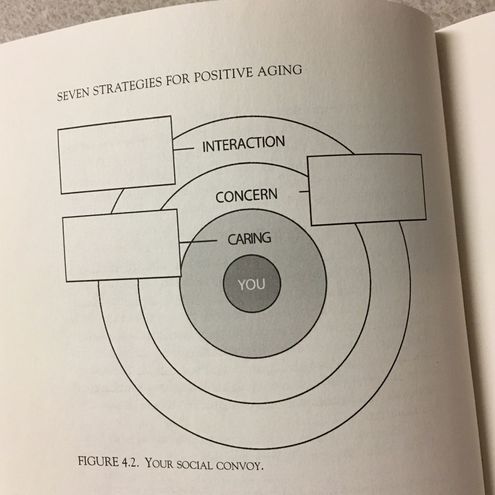

Now think about your own social convoy circle using the following diagram.

The interaction ring involves people who meet only the most superficial level of belonging. This area involves the interactions you have on a limited basis, like the neighbor you wave to, the coworkers you talk with at work, or people you encounter in your day-to-day travels like a bank teller or pharmacist.

The concern circle involves people who have not only interacted with you, but who have expressed concern about your welfare and in whom you are interested. This area may involve a childhood friend with whom you have regularly exchanged holiday cards, or a member of a senior center which you have attended regularly.

The caring and you areas of the circle involve people who not only interact and are concerned about you, but who care about you as well. These include family members, close relatives, your life partner, or your best friend. These are the highly meaningful people who have directly met your need to belong in the past and who are sources of support for you in the present and future. They are there when you need them, and they have been there through all three of the belonging behaviors: interaction, caring, and concern.

Now think about your own social convoy circle using the following diagram.

This social convoy has areas where you can fill in people you know who represent each of these categories. As you engage in this exercise, you will begin to appreciate how important that inner circle is to your well-being.

An important feature of the social convoy is that it also predicts how change occurs in the number and composition of your social network; the inner circle is the most stable and it is likely that you are highly motivated to stay connected to these people even if they are physically distant from you.

If you were to complete this social convoy model on a yearly basis, you would notice that people in your inner circle tend to be stable while those in the outer circles change more frequently.

An important feature of the social convoy is that it also predicts how change occurs in the number and composition of your social network; the inner circle is the most stable and it is likely that you are highly motivated to stay connected to these people even if they are physically distant from you.

If you were to complete this social convoy model on a yearly basis, you would notice that people in your inner circle tend to be stable while those in the outer circles change more frequently.

Part 2 - Positive Aging and Belonging

You must give and receive to strengthen relationships; put in the terms of science, the reciprocity of expressed interest, concern, and caring is a prerequisite to meaningful life-span relationships.

To develop belonging skills, we revisit the characteristics of Positive Aging:

To develop belonging skills, we revisit the characteristics of Positive Aging:

- Finding resources to engage belonging behaviors.

- Making life choices that strengthen interpersonal bonds.

- Employing flexibility to patterns and routines that bring us closer to others even in times of change.

- Emphasizing the positive to affirm relationship meaningfulness.

Mobilizing Resources for Belonging

Resources for belonging can be enhanced through selectivity, optimization, and compensation (SOC). It is well known that as we age, the number of our social relationships diminishes.

This is a form of selectivity; it occurs naturally through processes like the death of family members and friends, as well as when one’s more restricted living situation.

In the latter case, you may simply lose friends and acquaintances because you are no longer able to interact with them on a regular basis. Or your energy to sustain many friendships and relationships is no longer sufficient; it takes more time and effort to just keep up with your day-to-day routine and the few relationships that are part of that routine.

Research in gerontology suggests that it may (at times) be desirable to consciously disengage from people; a good analogy is a garden:

This is a form of selectivity; it occurs naturally through processes like the death of family members and friends, as well as when one’s more restricted living situation.

In the latter case, you may simply lose friends and acquaintances because you are no longer able to interact with them on a regular basis. Or your energy to sustain many friendships and relationships is no longer sufficient; it takes more time and effort to just keep up with your day-to-day routine and the few relationships that are part of that routine.

Research in gerontology suggests that it may (at times) be desirable to consciously disengage from people; a good analogy is a garden:

From time to time even your most prized plants need pruning, thinning, and even eliminating so that the healthy plants that remain have room to grow and mature. In fact, researchers in the science of aging suggest that for older adults to maintain healthy psychological functioning into their later years, it is required that they eliminate or “prune” superficial relationships to free up personal resources to devote to relationships that are more meaningful.

This phenomenon, known in the scientific literature as a socioemotional selectivity theory (Lockenhoff & Carstensen, 2004) is how Positive Agers find resources to sustain their sense of belonging with advancing age.

In other words, you have to let go of some relationships in order to preserve others.

Being more selective about relationships does not mean that you care less about people. It just means that when you no longer have the resources to sustain a large social network, you must make choices to preserve your own quality of life as it relates to belonging by focusing on the most important people in your life.

Being more selective may also help you discover new sources of meaning in close relationships that were not there before. In other words, by focusing on fewer people in your social network, you have added emotional resources to devote to those people. This kind of focusing opens the door to optimization, where your goal is to practice deepening your relationships with people who are the most meaningful to you.

This phenomenon, known in the scientific literature as a socioemotional selectivity theory (Lockenhoff & Carstensen, 2004) is how Positive Agers find resources to sustain their sense of belonging with advancing age.

In other words, you have to let go of some relationships in order to preserve others.

Being more selective about relationships does not mean that you care less about people. It just means that when you no longer have the resources to sustain a large social network, you must make choices to preserve your own quality of life as it relates to belonging by focusing on the most important people in your life.

Being more selective may also help you discover new sources of meaning in close relationships that were not there before. In other words, by focusing on fewer people in your social network, you have added emotional resources to devote to those people. This kind of focusing opens the door to optimization, where your goal is to practice deepening your relationships with people who are the most meaningful to you.

Making Life Choices That Strengthen Relationships

How we live our lives and where we choose to live affects, to a great degree, our social relationships and ultimately our sense of belonging.

Helping others is another approach to the world that is certain to enhance your sense of belonging.

How you spend your time is a life choice that impacts almost everyone, rich or poor. Are you a person who prefers to invest time in passive activities such as reading, watching television, or working jigsaw puzzles? Or do you prefer more active pursuits that involve others, such as attending classes, going to a social club, going out to eat, attending a class at your senior center, or dancing?

These are the kinds of behaviors that are manifestations of who you are, what you are like, and how you prefer doing things with others.

Helping others is another approach to the world that is certain to enhance your sense of belonging.

How you spend your time is a life choice that impacts almost everyone, rich or poor. Are you a person who prefers to invest time in passive activities such as reading, watching television, or working jigsaw puzzles? Or do you prefer more active pursuits that involve others, such as attending classes, going to a social club, going out to eat, attending a class at your senior center, or dancing?

These are the kinds of behaviors that are manifestations of who you are, what you are like, and how you prefer doing things with others.

Flexibility in Relationships

We are regularly engaged in assessing and nurturing our relationships, particularly our more meaningful ones.

You cultivate relationships by interacting and showing concern and caring. Sometimes a relationship is so strong and healthy that it needs little nurturing, but no matter how strong it is, it will not survive unless you intermittently assess it and determine what you can do to nurture it and keep it strong.

Relationships also change, and what might have strengthened a relationship at one point in time may not be as important later in life.

Sometimes relationships take unexpected twists and turns; these are discontinuities that call for your ability to be flexible in your thinking and in your behavior. It is not always possible to detect a problem or see an opportunity for enhancement.; All too often, people take close relationships for granted.

You cultivate relationships by interacting and showing concern and caring. Sometimes a relationship is so strong and healthy that it needs little nurturing, but no matter how strong it is, it will not survive unless you intermittently assess it and determine what you can do to nurture it and keep it strong.

Relationships also change, and what might have strengthened a relationship at one point in time may not be as important later in life.

Sometimes relationships take unexpected twists and turns; these are discontinuities that call for your ability to be flexible in your thinking and in your behavior. It is not always possible to detect a problem or see an opportunity for enhancement.; All too often, people take close relationships for granted.

Affirming What is Positive in Relationships

A basic building block of friendship is a positive affirming attitude. Almost everyone wants to be with others who help them feel good about themselves and their place in the world.

Dale Carnegie’s book How to Win Friends and Influence People is a great example of the power of a positive attitude in relationships. It centers on strategies designed to make yourself desirable to others by encouraging others to feel good about themselves. They become more interested in you as a consequence. The essential skill here is “interest in others.”

Consistent positive affirmation is the secret to strong relationship bonds and is at the basis of meeting your need to belong.

Whether maintaining a positive attitude or an affirmative approach to others, or avoiding negativity in relationships, discipline is required. It is essential that you check your thoughts about yourself and others. To gauge where you stand with respect to the valance of your interactions, you can identify some of these by contemplating the following question:

How might people who are in the inner circle of your social convoy describe you?

If the description is predominantly negative, then this is an area where you could exercise flexibility and begin changing the way you interact with others.

In addition, the following Positive Aging strategies can help you affirm the value in relationships.

Dale Carnegie’s book How to Win Friends and Influence People is a great example of the power of a positive attitude in relationships. It centers on strategies designed to make yourself desirable to others by encouraging others to feel good about themselves. They become more interested in you as a consequence. The essential skill here is “interest in others.”

Consistent positive affirmation is the secret to strong relationship bonds and is at the basis of meeting your need to belong.

Whether maintaining a positive attitude or an affirmative approach to others, or avoiding negativity in relationships, discipline is required. It is essential that you check your thoughts about yourself and others. To gauge where you stand with respect to the valance of your interactions, you can identify some of these by contemplating the following question:

How might people who are in the inner circle of your social convoy describe you?

If the description is predominantly negative, then this is an area where you could exercise flexibility and begin changing the way you interact with others.

In addition, the following Positive Aging strategies can help you affirm the value in relationships.

- Notice pleasant things about people with whom you are interacting and verbalize them.

- Share common positive memories with others.

- Smile. This is a nonverbal sign that you feel positive about other people.

- Listen. Sometimes simply listening can fill a need to belong in another person and can strengthen relationship bonds.

Part 3 - Positive Aging for Dealing with Loss and Loneliness

Loneliness is an emotion that you experience when you perceive that you are disconnected from or do not belong to your social network or social convoy.

An often-used definition of loneliness is that it is a form of emotional dissonance that results from a discrepancy between what you want from your support network and how you perceive that your social support network is functioning.

So, in a sense, loneliness is, for most people, a kind of self-focused negativity. Although loneliness can be a chronic emotional condition experienced at any age, it often appears in later life following a discontinuity in your support network.

An often-used definition of loneliness is that it is a form of emotional dissonance that results from a discrepancy between what you want from your support network and how you perceive that your social support network is functioning.

So, in a sense, loneliness is, for most people, a kind of self-focused negativity. Although loneliness can be a chronic emotional condition experienced at any age, it often appears in later life following a discontinuity in your support network.

Part 4 - Positive Aging for Grief and Bereavement

Grieving is a deeply personal and emotional process that follows loss. A grieving person is acutely aware of the power of belonging that is embedded in loss. Grief is a substantial discontinuity in one’s innermost world. It is difficult to personally reconcile this kind of loss.

Positive Aging considers death as a natural part of life and surviving and thriving following the loss of a loved one requires skills that involve mobilizing resources, making affirmative life choices, employing flexibility, and emphasizing the positives.

Researchers studying grief and bereavement have identified several key strategies that people use to get through this process.

The following points are adapted from the In Changing Lives of Older Couples (CLOC) study (Bonnano et al., 2002; Carr, Nesse, & Wortman, 2005; Boerner, Wortman, & Bonnano, 2005).

They mobilized their personal resources by tempering their emotional reaction to the loss through reframing it as a natural part of life course and by focusing on memories of their loved one which could give them strength to continue on with their journey in life.

They made affirmative life choices to stay engaged in the world. This involved getting support and meaning from family, friends, and others in their world whom they could rely on for emotional support and to help them transition from being couple to being single. They discovered new activities to engage in while single and they shaped activities that they traditionally did with their spouse in such a way that they could still find meaning in them, even though the spouse was no longer present.

They acted flexibly about the loss, using strategies such as humor by recalling memories that made them laugh or think fondly of their lost partner (Ong, Bergeman, & Bisconti, 2004). They altered their living contexts to make it easier to live alone by making changes such as downsizing their space needs, and eliminating unneeded objects (e.g., the second car).

They focused on the positives when they spoke to others and emphasized their new life following the loss. This was done not by denying that the loss occurred; in fact, several people cherished keepsakes from their departed loved one that reminded them what the departed spouse had given to them, including the hope that they might find happiness following the loss.

Learning to deal with loss is, for many, an ultimate lesson in the cultivation of a sense of belonging, even in the presence of permanent loss, through principles of Positive Aging.

Positive Aging considers death as a natural part of life and surviving and thriving following the loss of a loved one requires skills that involve mobilizing resources, making affirmative life choices, employing flexibility, and emphasizing the positives.

Researchers studying grief and bereavement have identified several key strategies that people use to get through this process.

The following points are adapted from the In Changing Lives of Older Couples (CLOC) study (Bonnano et al., 2002; Carr, Nesse, & Wortman, 2005; Boerner, Wortman, & Bonnano, 2005).

They mobilized their personal resources by tempering their emotional reaction to the loss through reframing it as a natural part of life course and by focusing on memories of their loved one which could give them strength to continue on with their journey in life.

They made affirmative life choices to stay engaged in the world. This involved getting support and meaning from family, friends, and others in their world whom they could rely on for emotional support and to help them transition from being couple to being single. They discovered new activities to engage in while single and they shaped activities that they traditionally did with their spouse in such a way that they could still find meaning in them, even though the spouse was no longer present.

They acted flexibly about the loss, using strategies such as humor by recalling memories that made them laugh or think fondly of their lost partner (Ong, Bergeman, & Bisconti, 2004). They altered their living contexts to make it easier to live alone by making changes such as downsizing their space needs, and eliminating unneeded objects (e.g., the second car).

They focused on the positives when they spoke to others and emphasized their new life following the loss. This was done not by denying that the loss occurred; in fact, several people cherished keepsakes from their departed loved one that reminded them what the departed spouse had given to them, including the hope that they might find happiness following the loss.

Learning to deal with loss is, for many, an ultimate lesson in the cultivation of a sense of belonging, even in the presence of permanent loss, through principles of Positive Aging.